On May 18, 2000, Congress signed the African Growth and Opportunity Act, commonly known as AGOA, into law. AGOA is a trade program meant to establish stronger commercial ties between the United States and sub-Saharan Africa. The act establishes a preferential trade agreement between the U.S. and selected countries in the sub-Saharan region. Initially approved for fifteen years, AGOA was reauthorized for ten years on June 25, 2015, by the Obama administration. In its current form AGOA will last until September 30, 2025.

It is important to emphasize that AGOA is a preferential trade agreement and not a free trade agreement. A free trade agreement is a treaty between two or more countries to establish a free trade area where commerce in goods and services can be conducted across their common borders, without tariffs or hindrances. A preferential trade agreement is a trade pact between countries that reduces tariffs for certain products to the countries who sign the agreement. While the tariffs are not necessarily eliminated, they are lower than countries not party to the agreement. It is a form of economic integration. The U.S. Department of Commerce describes AGOA as the “most liberal access to the U.S. market available to any country or region with which the United States does not have a free trade agreement.” AGOA in part was meant to establish a route for the U.S. to develop free trade agreements with certain African markets; however, this has yet to happen.

What is AGOA’s purpose?

Within certain sectors, AGOA is often looked at as a form of aid to developing countries. The U.S. government’s website says that it is “helping millions of African families find opportunities to build prosperity.” However, this image of trade as a form of aid is not entirely accurate. When needed, AGOA has provided the U.S. with preferential access to valuable commodities such as oil. AGOA has also served as a bargaining chip for the United States.

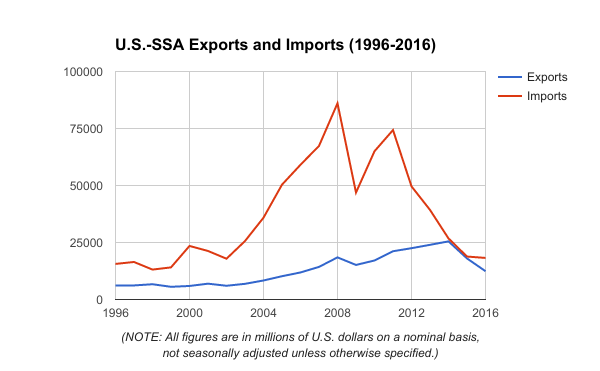

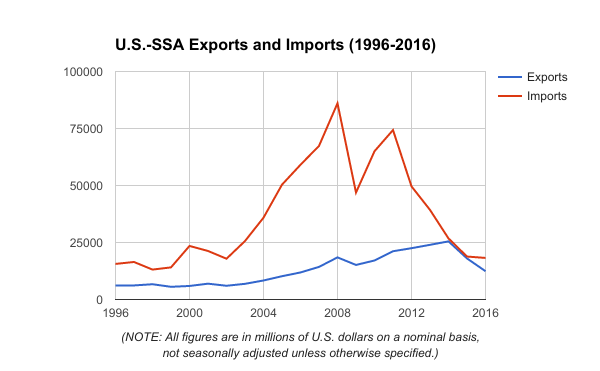

The trade relationship between the U.S. and sub-Saharan Africa has nearly always been skewed one way: the U.S. imports far more than it exports. AGOA didn’t change this. If anything, it increased the scale. U.S. exports to sub-Saharan Africa peaked in 2014 at $25.49 billion. The numbers for American imports are much higher, they peaked at $86 billion in 2008. (U.S.-Africa trade of products under AGOA reached its pinnacle in 2008 when it hit $66.3 billion.)

Those import numbers directly reflect American commodity needs. At the peak of American imports, between 2007 and 2008, the U.S. imported over one million barrels of oil a day from Nigeria alone. This is in direct contrast to the drastic drop in oil imports by 2015, when there were periods that the U.S. imported no oil from Nigeria. This trend affected other sub-Saharan oil producing countries as well. (The period between 2014-2015 represents the only time that the trade balance between the U.S. and sub-Saharan Africa was nearly even.)

AGOA is also a very useful negotiating tool. The U.S. president has the ability to rescind access to AGOA to any country if he were to determine that it is not working toward certain goals. In essence, the U.S. president has the ability to cancel the AGOA relationship with any partner nation if he feels that it doesn’t benefit the United States.

Most recently, AGOA was used as a negotiating tool just prior to its reauthorization in 2015. At the time, the South African government refused to let American chicken farmers export chicken products to South Africa. Accused of “dumping” low quality chicken products, the United States had not been allowed to export chicken to South Africa for over fifteen years. The South African argument was that American exports would destroy its local poultry industry by undercutting prices. On the American side, it was argued that this ban was a barrier to U.S. trade and investment. It was also argued that South Africa, with its advanced economy (though stalled), didn’t need a preferential trade deal (this goes back to the development side of AGOA). The renewal of AGOA, and South Africa’s inclusion in the renewed act, became questionable due to this one sticking point.

In the end, the South African government conceded and allowed the U.S. to export 65,000 tons of chicken products to South Africa. Trade with the United States was too important for South Africa to risk losing over chickens, especially as the U.S. is South Africa’s second largest export market. (South African exports to the U.S. in 2015 were valued at $9.1 billion. They consisted mostly of manufacturing materials, metals, and minerals.)

AGOA under the Trump Administration?

Based on the Trump administration’s largely anti-trade stance, there has been some worry that AGOA may possibly be on the chopping block. This, however, is highly unlikely. AGOA was passed originally by a republican congress in 2000, and was just reauthorized in 2015. It still maintains broad support across party lines, and even if targeted by the Trump administration, it is unlikely that Congress would approve its repeal.

AGOA is also not likely to be targeted for repeal because it is not a free trade agreement. While certain African goods are given preferential deals that reduce tariffs, sub-Saharan countries do not operate with blanket free trade and zero tariffs. In fact, the deal provides the U.S. with access to African goods and commodities that help drive the U.S. economy.

Additionally, it would be foolish of the Trump administration to give up a tool that provides the U.S. with so much negotiating leverage. As evidenced by the South African chicken trading incident, the U.S. government is able to use access to American markets to dictate trade opportunities in Africa. Countries like Kenya have already expressed worries that trade access through AGOA could be restricted. Traditionally, sub-Saharan Africa as a whole has critical problems with intra-state trade that increases dependency on large foreign trade partners. This regional trade gap provides greater leverage for the United States when participating in trade negotiations.

While it is doubtful that AGOA will be repealed, I would not be surprised if the new administration were to use the threat of removal from AGOA as a negotiating tool. Presidents have removed nations from the AGOA agreement before. The Trump administration doesn’t mean the end of AGOA, but it may mean that certain trade relationships are reevaluated.

*For more information on AGOA visit https://agoa.info/.